Writer Fariha Róisín and artist Ayqa Khan talk about growing up without intimacy, losing their virginity before marriage, and navigating faith and a sex life in the Western world.

Ayqa: Fariha, you are one of my few Muslim friends that I can talk to about sex. We both know that having sex before marriage is a forbidden sin; an action that would send us straight to the flame-y pits of Jahannam, or at least, this is what we’ve been told. But what if praying and sex are both parts of my life? Both give me comfort. Practicing and learning Islam helps me create my own morals and ethics. Sex allows me to take ownership of my body and explore my sexuality. I am comfortable with my curiosity, but often feel rejected by other Muslims, including some family members. To them, I am too liberal and too western; I could never be a “real” Muslim in their eyes.

Fariha: Yeah, I’ve struggled with the idea of what a “real Muslim” means, too. What does a real Muslim look like? Are real Muslims only those who wear hijabs, or have beards, or pray five times a day and know all the Surahs by heart? It’s very difficult to conform to an idea that feels very far removed from you and your reality.

My parents were liberal and never outwardly religious, but other Muslims in our community were quite the opposite. Religiosity was less important than spirituality to us, and my father would always say “Islam is a way of life, not a religion.” Even when my sister started wearing the hijab, at age 20 (I was thirteen), I felt like she was denying large parts of herself, and I didn’t want that for myself. As a young person I knew there was a part of me that wanted to see all of life for all it was; I wanted to experience things, even if they were haram. And oftentimes, my family didn’t agree with me.

Our home was complicated however. It was largely devoid of love and feelings in general. My parents were unhappy; my mom was severely ill; no one in my family knew how to express their emotions, and I wanted to feel something, from someone and I felt myself always seeking love wherever I could find it.

Ayqa: I feel that. My parents were never intimate with one another either. In fact, intimacy was practically forbidden in my household. So when I would watch other couples interact romantically in public, I was uncomfortable and confused.

The first time I saw two people kiss each other was at the movies. My aunt and uncle were babysitting me, an eight-year-old at the time, and when we sat down, my uncle asked me if he could sit next to my aunt. Twenty minutes later, they started making out. I didn’t know what was going on, so obviously, I started crying hysterically and couldn’t stop. Theater security eventually asked us to leave.

Fariha: It makes me so sad that physical displays of love were never introduced to you before then!

Ayqa: What hurts more is the fact that I can’t talk about such an important part of my identity with the people I love. My parents definitely think I’ve never had sex. My mom knows I’ve kissed boys because she has snooped through my journals, sure, but she probably thinks I haven’t gone past a steamy kiss. I don’t know how she would react if she knew I liked women, too.

Fariha: Yeah, it’s kinda heartbreaking that we can’t have that honest line of communication. There’s a part of me that wants to share things about my partners with my parents, especially my mom. This is the kind of relationship I always craved when I was younger and saw my white friends talking to their moms about boys and get guidance from them. I’ve come to terms with the fact that even though I hate it, I have to hide large swathes of my life from my parents. A lot of us just accept that it might be safer, for both parties, if we just pretend to be normal. I love my parents, and I understand that it’s hard for them to comprehend. They come from a different headspace.

Ayqa, how did you come to realize you liked both men and women? After my abortion, I primarily only dated and slept with women. It felt safer. My sexuality is fluid; I don’t like defining it. I hate how everything has to be explained within a framework or a concept. A couple of years ago my sister asked me if I’d ever slept with a woman, and I denied it — earlier this year she asked me again, and I came out to her and told the truth. It’s funny, my sister has been this spiritual faerie my whole life; so pure, so good, so Muslim. But, I think that the more openly honest I am with myself, the more honest she’s becoming with herself, too. I’ve watched her being more open to ideas even about her own sexuality, and what that means.

Ayqa: Well, I have always been attracted to women. Growing up, I was constantly surrounded by heterosexual people and thus never really knew how to fully engage in that part of me that desired women. I didn’t know where to start or what to do. I almost dismissed that part of me because I didn’t know how to navigate such a primarily heterosexual space, a space where fluidity did not exist. Towards the end of senior year in high school did I allow myself to accept those feelings of desire and act on them, when I met someone. I met a girl who allowed me to embrace all parts of myself, and in doing so, did I begin to understand my own sexual fluidity.

It’s funny you mention your sister because when I would try to engage with my older sister about my questions, she would shy away and “joke” about how I’m a “hoe.” I wanted advice and guidance — navigating a sex life as a Muslim is difficult! — but I ended up having to figure out my body and sexuality on my own. The more experiences I had with different men and women, the more I started to understand myself. Talking to my partners about the way we had sex, what we liked, what we wanted really helped me feel comfortable with my body and thoughts alongside making sure I was doing the best I could to make them feel comfortable. Doing so allowed me to feel in control and gave me room to be myself. But I’ve always kept Islam and my sex life separate.

Fariha: Yeah, if you don’t have anyone to turn to, you’re forced to figure it out on your own. When I was eight years old, my friend’s mom took us to see Titanic and I saw my first naked body — Kate Winslet’s. It was thrilling. My friend’s mom asked us to cover our eyes, but I peeked through my tiny fingers to see Kate’s voluptuous body. The only other time I felt that alive was while reading some erotic fiction in my early teens. It left me feeling buzzed, like a bulb went through my body. But I kept these feelings to myself because I was young and didn’t know if I was supposed to be feeling this way. Homophobia was rampant at my all-girls school, so my sexual exploration had to be almost entirely a secret.

Ayqa: Oh wow, for me my sexual exploration started in middle school, my peak puberty years, when I started masturbating. I would take baths as often as possible and would almost always be overcome with a desire to touch myself. I gave myself an orgasm before I knew what an orgasm was. Embarrassed of what others might think of me if I told them, I kept my bath time rituals a secret. Though, I was so clueless at the time, I remember googling: “Can you get pregnant from an orgasm?”

Fariha: Ha! I can’t even remember when I first O’d, isn’t that sad? I definitely never really masturbated until my friend gave me a duck vibrator for my eighteenth birthday. I went home and just masturbated three or four times. To me, it was important to find pleasure that’s holistic, and not shameful.

Ayqa: Yeah, exactly! I figured pleasuring myself would be in line with Islam: I was giving to myself, instead of seeking it out through acts that were considered haram. But the more I googled, the more I realized that some Muslims disagree — but that didn’t really stop me.

Fariha: I think it’s absurd that women — I mean all women, not just Muslim women — are denied this part of ourselves. In Muslim communities, it’s taboo to talk about sex openly and there’s a strong emphasis on seduction of the female form. This kind of gendered relationship with sex stifles many Muslim women’s relationship with pleasure. You’re not supposed to talk about sexual desires, so suddenly pleasure is cloaked in shame. Something so natural becomes a curse.

Whenever I would ask other Muslim friends or family members about sex or intimacy, their responses were dismissive: “Just don’t think about it!” But I couldn’t stop thinking about it. My mom, especially, made me feel dirty about my body. She would berate me when I was just a kid (I was six years old) saying that I was asking for sex because I didn’t cross my legs. She would say things like, “You secretly love the attention, don’t you? Slut.” In my early teens, if I wore anything remotely form-fitting (usually accidentally), she would chastise me, yelling that all I wanted was the dirty glares of men. Her violence was a product of her illness, but I think her struggle with mental illness was rooted in her parents’ denial of her sexuality, and her interest in a deeper exploration of herself through art and culture.The more I understand my mom, the more I see our similarities. Like me, she wanted to explore different parts of herself, but was never allowed to because of the limitations her community imposed upon her.

Fariha: I went to an all-girls high school where the idea of sex was pretty pervasive, and most of my friends were beginning to sleep with their boyfriends around age 15. My parents had taught me that virginity was sacred and holy, so I was naturally judgmental of my friends. While they were exploring themselves, I just felt really grossed out and disappointed. I never felt jealous — I never had FOMO — I was sincerely trying to be a good Muslim. Then one day I just didn’t know what a “good Muslim” meant anymore, and I felt frustrated that I kept trying to hurt myself for the desire I felt. I had met a guy that I liked, so I just took the plunge, praying for my sins as I performed them.

When I did start having sex, I figured my mother was right: I was evil because I had betrayed everyone around me, and I had succumbed to an earthly pleasure. I thought I had passed some kind of sacred threshold; Islam didn’t matter anymore, because I thought I couldn’t be Muslim anymore.

Ayqa: Why do you think you felt like that?

Fariha: Well, because I had a very limited idea of what being a Muslim meant. Back then, it was largely tied to ritual for me — prayer, fasting; the five pillars. Even though my father had always taught me that Islam was a philosophy, I felt like there were very serious borders I couldn’t cross, sex being one of them. My mother was struggling with herself all throughout my teens, and my father wasn’t around, my sister was seven years older and dealing with her own shit, too — so I didn’t really have anyone to turn to.

There was no one to stop me from having reckless sex without protection, to stop me from hurting myself, to stop me from getting pregnant. I wish someone had told me that sex is ok, that it’s normal and human nature. Then, maybe I wouldn’t have fallen so deeply into my own destruction and depression.

Ayqa: I’ve been there too, Fariha. Sometimes, I don’t feel any sort of guilt or remorse for my actions; then other times, sex leaves me in a dark place — a place where I begin to question and dissect my own beliefs.

Since I was forced to guide myself through puberty and my sexual awakening, I ended up always relying on my partners for advice and direction. I figured they would have all of the answers; they were the only ones who could save me from the trappings of my religion.

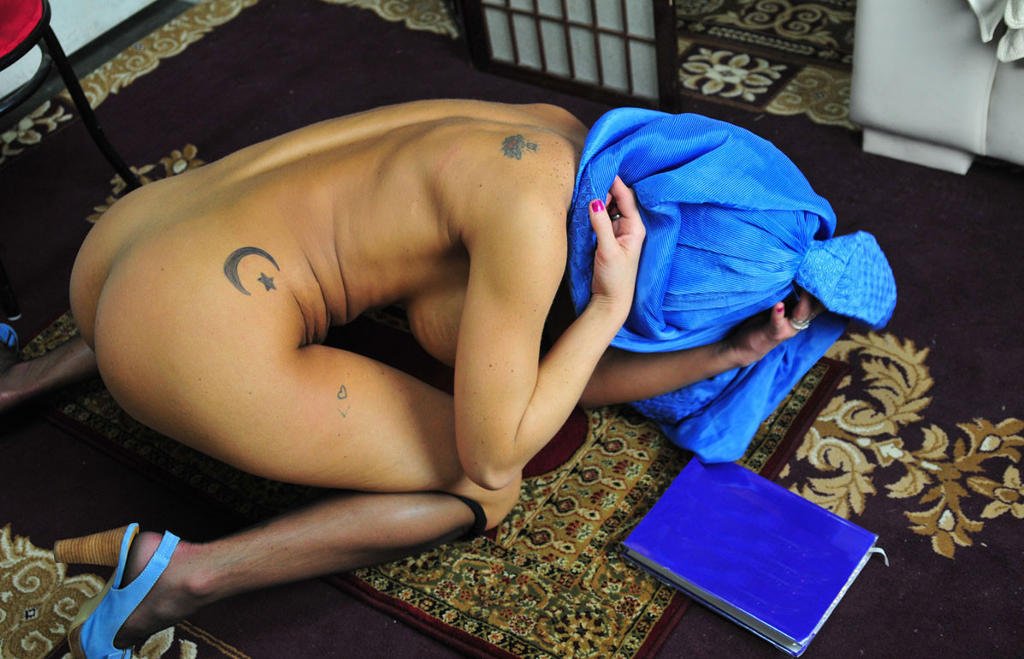

In my last relationship, I subconsciously dropped most of my routine and revolved a new life around my partner. We shared interests and hobbies, like music and art, but sex was a huge part of our relationship. If we weren’t intimate, everything else felt meaningless. And yet, I’d find myself in their bed, after they’d gone to work, talking to Allah, “I know this doesn’t feel good but I don’t know how to leave.” I was so exhausted from needing this person that I’d slip into praying in these moments, begging God to show me the truth. There was a part of me that didn’t want God to abandon me even if I knew what I was doing was “wrong.”

Fariha: That’s so real — the fear of losing God.

Nowadays, even though I live my life by my own principles, I feel closer to Islam than ever before. It finally feels like mine — not just something I’m trying to uphold, badly. I don’t want to live my life thinking that God is forever punishing me, when I could live a full life, and understand, and know, that God is always there and loves me.

Ayqa: Oh, there have been a few times I’ve felt like God was punishing me, too. I went to the gynecologist for the first time when I was dating my first boyfriend and it was maybe three months into our relationship. I felt scared and liberated during my first visit. I was in an unfamiliar place where a very personal part of myself was going to be examined and spoken about so openly. I had never really spoken about sex with my friends, because I didn’t have many partners. I didn’t fully know much about vaginas and sex until I started having experiences, and with them I developed a stronger relationship with my body. Being in that office alone and lost showed me I was there to take care of myself, because if I didn’t, no one else would.

A few days later I got a phone call from a doctor: I tested positive for Chlamydia. I immediately had a panic attack. I wanted to run into my mom’s room and cry. I wanted her to hold my hand and take me to the gyno and tell me it was going to be okay. I wanted her to validate me and my pain, to tell me that I did nothing wrong and that this all would go away.

For a moment, I thought God was punishing me. That I deserved all of this because I decided to have sex. But that moment was short-lived. My next thought was that I needed no one but myself.

Fariha: Did you talk to your partner about how you felt punished by God?

Ayqa: Well, I berated him for not telling me about his STI, but I did not tell him about this conversation with God. Islam, in general, was a subject my partner and I rarely discussed, and when we did, we barely skimmed the surface; it felt too complicated for him to digest, so I just avoided it.

Fariha: Which makes sense, too, when you’re unsure of where you stand you avoid talking about it. I used to do this because I was so embarrassed of being Muslim, and feeling Muslim, when I knew I didn’t seem Muslim enough. Though, I think more so, I just didn’t know what to say, how to defend myself. Going forward, I think it’s gonna play an important role in conversations I have with future partners, because I feel way more comfortable in all of my identities now.

In the past, I’ve always felt in between two worlds: I wasn’t Muslim enough to be a true part of the Muslim community; at the same time, my religion was too much for my non-Muslim friends to understand. I think that’s why I write — to create the community I never had. To protect the young women, femmes who need this like I needed this when I was younger. I want us to safeguard our bodies, and our souls, so that we don’t get into abusive relationships, or put our selves on the line.

Ayqa: Communities aren’t always kind.

Fariha: They’re not. Humans like to place other humans (especially women/femmes) into boxes, which is very destructive. Either you are this or that — you can’t be both. Take, for example, the time a woman on Twitter told me I wasn’t Muslim because I didn’t wear the “required” head-covering. Just by looking at me, she had placed me into a box. A box unworthy of being a Muslim. It was upsetting.

I think that if we can teach young girls that their bodies are their own, not their religion’s, or their families’, or their partners’, then maybe we can move to a place where women have a real, holistic understanding and acceptance of who they are. I don’t feel the need to explain myself to any community anymore. I have to come to terms with my own life, my decisions — for myself. Not for everyone else who wishes to control me. I’ll decide how to live my life and follow my faith. And other Muslims should learn to do the same.

Ayqa: I feel the same way about my relationship with Islam: it’s between me and Allah, and no one else. I am going to practice what I feel is right — even if my actions feel contradicting.

A “good” Muslim is one who prays, eats halal, practices the five pillars of Islam, practices abstinence; a “bad” Muslim is one who drinks, has sex, eats pork. I don’t believe in either, and I think such dichotomies need to be demolished. I was born with a history and tradition that will never leave me. I am also a child of the West. I like having a glass of wine — and I like praying. I am affected by the implications of Western society alongside the placement and practice of Islam in my personal life, and life as a member of Western society. Here, in North American, we are given a lot of space to explore ourselves without deliberate consequences. We are lucky for this, so why begin to dismiss our existences because we don’t fit a mold? There is no formula to get into heaven. It’s between you and Allah.

This article originally appeared in Muslim Women Speak on Medium and is republished with permission from the author.